The Cottingly Fairy Photo Hoax

- Melissa Gouty

- Aug 19, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 22, 2020

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle totally believed

Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book

I couldn’t believe it. For nearly a quarter of a century, I thought that Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book was a marvelous picture book filled with interesting artwork and a fun story about a mischievous young girl who sees fairies and then captures them by slamming them into a book, preserving their images forever on the pages.

Oh my! Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book is so much more than the whimsical art of fantasy fairies. Since I had always been enamored by the pictures, and since my children and grandchildren never had the patience to sit listening to the story past the first few pages, we got into the habit of turning pages faster and faster, always watching for the next fairy picture to appear.

In a stroke of literary karma that sometimes happens to working writers, I pulled that book off my shelf today and read the WHOLE story. If only it hadn’t taken me twenty-four years to read the entire book cover-to-cover!

Delighting two generations

Years ago, my daughters had been mesmerized by the illustrations of various fairies. Later, my grandkids, five of the six of them boys, laughed at the pictures, pointing out the occasional flash of a bare fairy bottom or the sight of a loose fairy breast. They remarked on the colors of fairy blood, the big splayed toes, the three-fingered-one-thumbed hands smashed onto the paper.

The fairies had names — Florizal, Mogcracker, and Skamperdans, just to name a few. Some were beautiful. Some were ugly. Laughing. Surprised. Angry. Taunting. Those little fairies display every kind of emotion, depicted in lush and flowing art. Earthy greens, browns, and blues linger on the pages, remnants of once-fluttering fairies now reduced to smears on dry paper.

I was afraid the idea of crushing fairies to their death would be scary for the children. Silly me. None of my offspring in either generation were afraid. They were amused, and I’m sure it was because even at their tender young ages, the KNEW this was just a story. NOT real.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle truly believed in the existence of fairies

My grandkids are smarter than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Turns out, Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book is a parody of an actual fraud perpetrated more than a hundred years ago. One that the brilliant creator of Sherlock Holmes believed.

And that literary karma I was referring to?

I just had written about two other literary frauds, The Great Poet Ern Malley (Who Never Existed) and The Importance of Being Authentic — and How to Do It. With the idea that everything happens in threes, I’d discovered another true-but-weird-story hovering between hoax and hysteria.

The Plot of Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book

A young woman begins to see fairies, but to her dismay, no one takes her seriously. She begins to snap her book on them, discovering that if she’s quick enough, she can squash them inside and make people believe her.

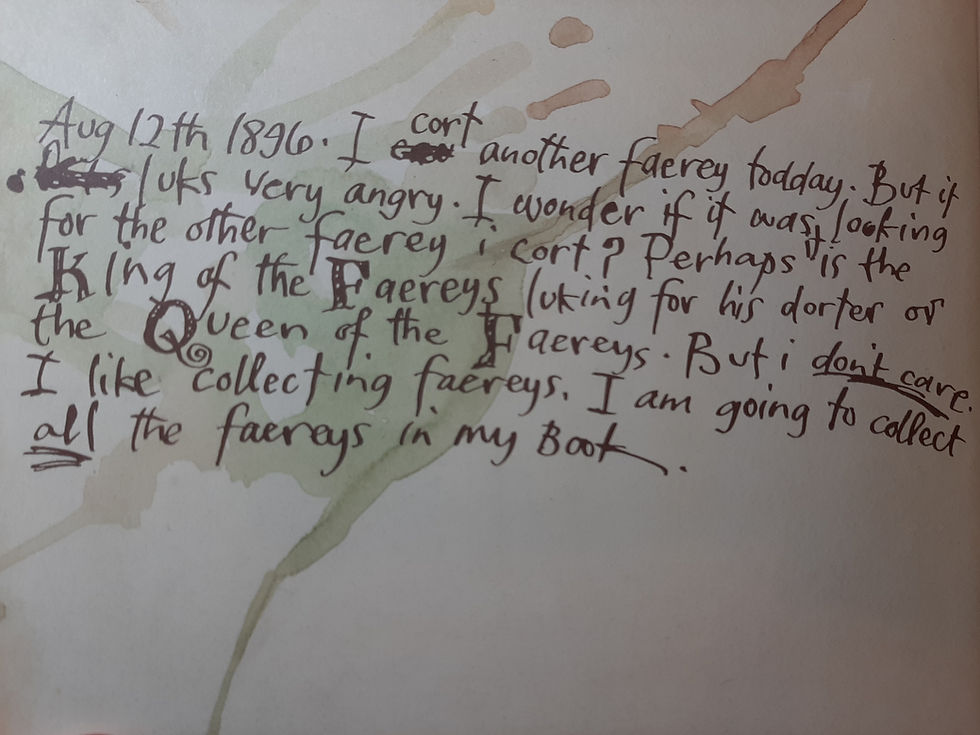

Written in diary form, the book progresses from the writing of a very young child in 1895, filled with misspellings to the perfectly scripted entries through 1912. Angelica, the writer, says,

“July 6th 1895. Nanna wuldnt bleive me. Ettie wuldnt bleive me. Auntie Mercy wuldnt bleive me. But i got one. Now theyv got to bleive me.

July 7th 1895. I showed my faerey to Ettie but she sed Nanna would be cross bekaws my book is for pressing flowers in not faereys so i wont show it to anybody I am going to fill my book up with faereys SO THER.”

Good thing I never read the whole thing out loud to the children. As Angelica ages, she continues to blame the fairies for everything, including her behavior, and as an adult, I understand so much more than the kids would. After Angelica’s cousin finds a photo of a fairy she has taken in a newspaper, Angelica is made a laughing stock. No one believes her picture. To escape the humiliation, she takes a trip to Italy.

But those dratted fairies are there too, doing things that make her behave oddly. Her reactions to the fairies are misconstrued, resulting in an amorous Lord Crowley coming into her stateroom and making advances. The fairies make her say and do things:

“15th May 1907: I will not go into further details of this most unhappy night. Suffice it to say that those wicked fairies flew around me, tickling me and touch me with their wicked little hands so that I cried out with laughter or gasped for breath on more than one occasion, thus fuelling His Lordship in his mistaken impression that I was encouraging him!….

How long this orderal continued, I am not sure. But I grew weak and trembling with my exertions and one of those impudent fairies seemed to be right inside me — tickling me from within so that I could scarce think and scarce knew what was going on….”

Ahem.

Spiritualism and Theosophy

Think about the turn-of-the-century Victorians. Spiritualism, the belief that spirits of the dead surround us and are capable of talking to us, is rampant. In 1897, an estimated 8 million middle and upper-class people are believers.

Throw into the spiritualism mix a belief in theosophy: a belief that the spirit is always trying to escape the bounds of the body through some mystical experience.

One hundred years later, it’s hard to believe that there could have been any credibility at all attached to the following story, but here goes…

The hoax:

Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book is a parody on the Victorian beliefs and the true episode of the Cottingly’s Fairy Photos.

In 1917, two girls, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, were playing around. Elsie’s father was a hobbyist photographer with his own darkroom, and his daughter had worked in a photography studio. Using his camera, the girls took some pictures that looked like they were with fairies.

Elsie’s father dismissed the photos as one of her artistic endeavors. Elsie’s mother, backed up by statements from the girls, believed those photos to be real.

In 1919, Mrs. Polly Wright took two photos to her meeting of the Theosophical Society. Believe it or not, the lecture that night was on “fairy life.” Edward Gardner was a bigwig in the organization, and he was ecstatic over the photos, believing that the

“…girls had not only been able to see fairies, which others had done, but had actually for the first time ever been able to materialise them at a density sufficient for their images to be recorded on a photographic plate…”

The rest, as they say, is history…

Gardner took those pictures to a photography expert named Snelling who said there was no evidence of tampering. He took them to Kodak for verification. While the technicians at the film company couldn’t find evidence of faking, they didn’t believe the photos were genuine.

Enter Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, an ardent believer in spiritualism, saw the photographs that Gardner had published in a spiritualist magazine, and he teamed with Gardner to validate the photos as proof that a different kind of spiritual existence was, in fact, a reality.

Gardner visited the Wrights again, gave the girls some different cameras along with lessons on how to use them, and left them alone because the girls stated that the fairies wouldn’t appear while others were around. (Really.)

Three more photographs emerged after that visit and were sent to Doyle, who responded,

“My heart was gladdened when out here in far Australia I had your note and the three wonderful pictures which are confirmatory of our published results. When our fairies are admitted other psychic phenomena will find a more ready acceptance … We have had continued messages at seances for some time that a visible sign was coming through.”

The gullible public

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had been commissioned to write an article on fairies for the 1920 edition of The Strand, a well-reputed magazine of popular fiction. Doyle included the first two fairy photos in his December 1920 story. The edition sold out in two days' time.

Despite the skepticism of many experts, a fervor existed around the photos, and in 1921 Doyle used the last three photos for a second article in The Strand, a prelude to his book, The Coming of Fairies, published in 1922.

In 1966, Elsie suggested in an interview that she may have been able to photograph her thoughts, re-igniting the interest in the photos from forty-four years before.

But by 1983, both girls admitted that they had, indeed, seen fairies. They had, however, faked the photos.

Little matter.

All of the photos and the cameras with which they were taken were purchased at high prices and are now on exhibit at what is now the National Science and Media Museum because of the national fervor they had caused.

Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book

Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book delights me and makes me smile now more than ever. Knowing the history of this fraud brings new meaning to the clever parody written by Terry Jones and stunningly illustrated by Brian Froud.

Fact truly is stranger than fiction.

Want a memorable gift for someone you care about? If you love interesting art, are interested in the Victorian era, or are fascinated by hoaxes, get Lady Cottington's Pressed Fairy Book.

Read about more hoaxes:

No matter what kind of books you like, you'll gain insights from articles in Book Talk.

1 Comment